COVER STORY

HIRABAI BARODEKAR - The voice that could cure a sick man

DEEPAK S. RAJA

Hirabai Barodekar (1905-1989) was amongst the most distinguished and popular Hindustani vocalists of the 20th century, and almost certainly the most melodious female voice heard in recent times. She was the eldest daughter of the Kairana gharana founder, Ustad Abdul Kareem Khan, but trained primarily by her father’s associate and Kairana co-founder, Ustad Abdul Waheed Khan. She exploded upon the scene while the giants of the pre-independence era still ruled the concert platform, and remained amongst the most respected vocalists thereafter, sharing the stage with the likes of Amir Khan, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, and Kesarbai Kerkar.

In a busy career spanning over 45 years, Hirabai captured the hearts of millions with her renditions of khayal, thumri, natya sangeet, bhava geet, and bhajans on the concert platform, in the regional theatre, through radio broadcasts, and through commercial recordings. Even after her voluntary retirement in 1973, she accepted the position of a Resident Guru at the ITC Sangeet Research Academy, which she served until 1976.

SPECIAL FEATURE

REMEMBERING MEHDI HASSAN - The Shahansha-e-Ghazal

MANOHAR PARNERKAR

13 June 2015 marks the third barsi (death anniversary) of Mehdi Hassan (from here on we will call him Khan Saheb). The spontaneous outpouring of grief that resulted in the wake of his sad demise three years ago convinced me that both in life and death, Khan Saheb still remains one of the best-loved, most written-about musical superstars to come from the Indian sub-continent. Every low-brow, middle-brow, high-brow, and even the philistine average Indian Joe (and I suspect, decidedly more than that, his Pakistani counterpart) would have at least heard of Mehdi Hassan, if not actually heard his sublime ghazal music; an astonishingly large number of them would have also heard, and loved his Ranjish hi sahi and/or Rafta rafta woh meri. And virtually every aspect of the legendary ghazal singer’s life and art, elaborately documented by music writers on either side of the Indo-Pak border, has all been in the public domain now. And here are some of the aspects that these writings often bring to my mind.

Khan Saheb’s strong Indian roots and, in particular, his Rajasthani origins; his initial struggle in Pakistan, first as a car/tractor mechanic, and then as a radio artist/film playback singer; his triumph over these adversities culminating in his ultimately being hailed universally as Shahansha-e–Ghazal; his sachha sur and exceptional command over tala; his highly skilled use of musical ornamentation like taan, meend and gamak; his husky, velvety, mellow baritone voice that could seduce any listener anywhere in our part of the world – from Kathmandu to Kozhikode, and Mumbai to Multan; his impeccable diction of Urdu language; his intuitive feel for the bhava (emotional content) of great Urdu poetry; his remarkably beautiful delivery of a verse in measured cadences and with highly articulated phrasing; his deep knowledge of our classical music – reflected in the highly innovative use of the most appropriate ragas in many of the memorable ghazals that he set to music; his astounding ability to move – and touch – the initiated as well as the lay listener at three levels namely, sensuous, expressive and sheerly musical.

TRIBUTE

T.S. SANKARAN (1930-2015) - Mali’s Ekalavya

UDAY SHANKAR

Born on 28 October 1930, T.S. Sankaran was the son of flute vidwan T.N. Sambasiva Iyer from whom he imbibed music and flute playing at a very tender age. The family hailed from the village of Sathanur in the musically and culturally rich Kaveri delta. Family folklore dating back a couple generations speaks of associations with the illustrious 19th century son

of Sathanur, musician Panchanada Iyer, a disciple of Muthuswami Dikshitar.

Later on, “Sankaran sir” (as he was to all who knew him) was a loving and dedicated disciple as well as perhaps the closest confidante of the legendary Mali. “Mali sir” was a native of Tiruvidaimarudur, a mere stone’s throw from Sathanur. In a conversation with the poet Vali, published in the Tamil weekly Kumudam sometime in the 1960s, Mali hailed Sankaran

as an Ekalavya who perfectly imbibed his style without any direct instruction.

ESSAY

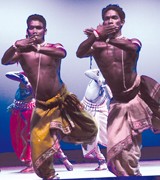

Odissi and Chhau – a comparison

ILEANA CITARISTI

Odissi and Chhau dance are two products of the rich cultural history of the state of Odisha. They represent two important aspects of this history and are indicative of the two major trends that characterise the region, the religious or bhakti component and the martial one.

This article only refers to the Mayurbhanji variety of Chhau dance. Although two branches of the same tree, the two forms of dance had different and almost contrasting paths of development. While we can trace the history of the Odissi form to the nartaki depicted in the Rani Gumpha cave of Udayagiri (200 BC) considered the most ancient dancing representation in stone, we do not have many documents relating to the emergence of Chhau dance before the 18th century AD. Odissi had almost disappeared by the beginning of the 20th century, to be revived only after Independence. Chhau, on the other hand, had reached its climax by the beginning of the 20th century and lost its lustre with the merger of the Mayurbhanji state in 1949. It had lost the patronage of the Bhanji royal dynasty, and it took some time before the new government came to its rescue.