COVER STORY

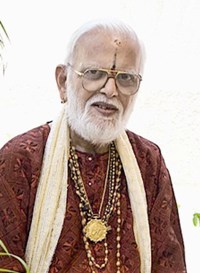

T.K. GOVINDA RAO -LAKSHMI SREERAM

He made the Musiri bani his own

The teacher is seated on a generous sofa. Students of various ages squat on the floor, singing in hush hush tones. Everyone’s talam is soft. No one dares to sing loudly, yet the slightest lapse is noted by the teacher, who identifies the culprit with unerring accuracy and makes a sharp remark. First the varnam – in 4 speeds (vilamba kalam, tisram, madhyama kalam and tisram), then kriti after kriti in that particular raga, each followed by many rounds of kalpana swara – until the less stout-hearted among the students start crying in the heart. “Ayyo porum!” The expression “bendu nimundidum!” comes again and again to mind as the next round of swaraprastara starts. The class had begun at 11 am, and at 2.30 pm, the teacher, 80 years old, is still raring to go, while the students have started squirming and twisting and stretching their bodies. Such is a weekend morning in the house of Sangita Kalanidhi T.K. Govinda Rao.

Torchbearer of the exquisite Musiri bani, TKG is justly proud of his lineage. At 80, he has a sharp mind and ear, and, until a recent health setback, he spent a few hours working on the computer each day compiling his fifth book of compositions. His work in bringing out volumes of the compositions of Carnatic music composers with notations transcribed in both Devanagari and diacritical Roman scripts is a monumental achievement.

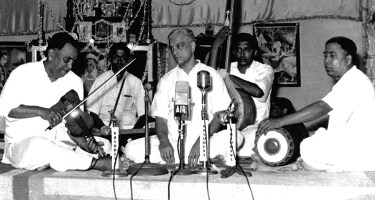

GNB CENTENARY

The GNB bani – Part III - – LALITHA RAM

Niraval

GNB invariably did niraval on a whole line of verse, unlike some other musicians who would take up only a part of a line for treatment. He did not shorten even long lines like Tapatraya harana nipuna tatvopadesa kartre. He did not always rely on the convenience of vowels – as in the case of agama nigama in Nannu brova – in the verse for niraval. He was expert at bringing out the raga bhava in relatively consonant-filled verses as well, as in the case of the line kalilo matala nerchukoni kantalanu tanayula brochudai in Nenarunchinanu in the raga Malavi. GNB also often did niraval on aptly chosen lines, which were however different from those traditionally purveyed. Examples are his choice of the line Tapatraya harana nipuna, rather than the usual Vasavadi sakala deva vanditaya. His use of the first two syllables ‘ta’ and ‘pa’ as swarakshara-s (dha pa) was his trademark that listeners grew to anticipate. Likewise his deviations from standard practice in kriti-s like Nidhi chala sukhama, Meenakshi memudam proclaimed his creative genius.

MAIN FEATURE

THE SHEHNAI

Auspicious instrument, inauspicious omens - DEEPAK S. RAJA

Only two generations ago, the shehnai was perhaps the most widely heard instrument in northern India. It has, for long, been an integral part of tribal, folk, religious and ceremonial music on the subcontinent. In the latter half of the twentieth century, Ustad Bismillah Khan (1916-2006) took it to the peak of popularity on the concert platform. Befitting the status of the instrument as the “mangala vadya” and the Ustad’s early distinction, it was his recital that heralded the dawn of Independence from the Red Fort on 15 August 1947, and later launched the Indian Republic on 26 January 1950. The instrument could well have qualified as the ‘national instrument’, if such a thing existed. By the time of Bismillah Khan’s departure, however, the instrument was gasping for breath.

The instrument belongs to the oboe family of beating-reed aerophones. Instruments of this variety and almost identical design are found in all parts of India. The nagaswaram, an instrument of the same family, and known by various names, has comparable status in India’s southern peninsula. Even in north India, the instrument has several names. Some names are of Sanskrit origin, and indicate ancient Indian ancestries. Others describe it as a ceremonial instrument for processions and court assemblies suggesting feudal patronage. Some have a Persian ring to them, and hint towards Middle Eastern extractions. And, some others, derived probably from folk and tribal cultures, describe only its physical form or its shrill piercing sound. Despite confusing signals, organologist, B.C. Deva, believes that the shehnai is an entirely Indian instrument.

REAR WINDOW

KAILASANATHA TEMPLE IN KANCHIPURAM

The dance of Siva in stone - CHITHRA MADHAVAN

One of the most sought-after temples on the tourist circuit in Tamil Nadu is the unbelievably beautiful Siva temple of Pallava times in Kanchipuram, now known as the Kailasanatha temple. Constructed in the eighth century, during the reign of Narasimhavarman II, better known by his title Rajasimha (c. 691-728 AD), this temple, almost completely built of sandstone, and known for its architectural excellence, is a treasure-house of Saivite iconography. The original name of this temple, eulogised in an inscription here as “one that robs Mount Kailasa of its beauty”, was Rajasimheswara.