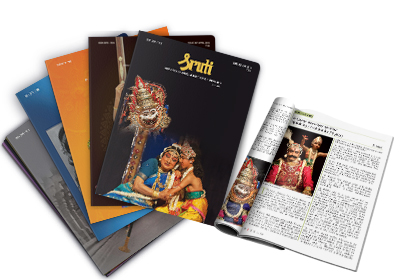

COVER STORY - A marvel of tradition and talent by SUJATHA VIJAYARAGHAVAN

The following profile and other articles on V.S. Muthuswami Pillai were written around 1990-91 and handed over to N. Pattabhi Raman, Founder and Editor-in-Chief, Sruti. Hence the natyacharya is described in the present tense. His end was sudden and took away some of the incentive in bringing these articles in print. As I edit them now I see and hear him and marvel once again at the high energy of his communion with the art. The four hectic days when I interacted with him to format and anchor his presentationfor the Parampara Seminar of Sruti in 1989 afforded a rare insight into the art and personality of the master. His fa reaching influence on young dancers, dance teachers and choreographers has been apparent over the last two decades. Montpellier. A village in France, where the annual Festival International Montpellier Danse is underway. Encomiums are showered on the recipient of the title Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres given to a great artist every year. Not a word of it is understood by the genial maestro of seventy years, standing straight as a ramrod to receive the honour. As the medal is pinned literally to his chest, he winces ever so slightly through his smile. Vaitheeswaran Koil Sethuraman Muthuswami Pillai, the first Bharatanatyam guru and the first person from Tamil soil to receive this honour, had indeed covered long distances in space and time to arrive at this point in the twilight of his life. It had been a life of waiting — waiting for the right guru, the right disciple, waiting to be understood, to be appreciated, to be honoured. With hope sometimes, with despair mostly, he had waited and persevered with unflinching faith in his own creative instinct. Ultimately when the honours came, they came not as single spies but in battalions.

SPOTLIGHT - Not by voice alone by CHITRAVINA N. RAVIKIRAN

As one who is first a passionate rasika and then a performer and pedagogue of both vocal and instrumental music (and also as one who has composed for both), I have always been fascinated by the complementary roles of these in our wonderful system as well as other systems such as Hindustani, Jazz or Western classical. While vocal music strikes a chord with most listeners familiar with a system, it is the abstract instrumental music that draws people from outside to it. For instance, in Western classical music, orchestras are heard much more universally, while vocal-centric operas attract a decidedly smaller subset. Hindustani music (which is ‘Indian’ music to most people on this planet) is to this day, symbolised by the sitar and tabla, a sway that their greatest vocalists are yet to match. But then in north India, high quality instrumental music attracts excellent crowds even today. Understandable scene But in Carnatic music which is composition-centric, it is quite understandable that vocal music should occupy the primary place in listeners’ hearts. Vocal music is generally taught to even those who aim to specialise in instruments. Some of the greatest instrumentalists such as T.N. Rajaratnam Pillai (nagaswaram) and Budalur Krishnamurthy Sastrigal (gottuvadyam) could give frontline vocalists a run for their money.

NEWS & NOTES - A dancers’ retreat – to advance their art by VIDYA SARANYAN

The gopuram of the Pandurangan temple beckoned from afar. Nestled in the midst of green fields the temple complex was the hub of cultural activities for the next three days as the Natya Sangraham camp progressed in the first week of February, with an eclectic mix of dancers, musicians, experts, and ‘sahridaya-s’ – that all comprehensive term for art lovers. Natyarangam, the dance wing of the Narada Gana Sabha Trust, has been conducting the camp every year since 2000 at the Dakshina Haalaasyam at Thennangur. The camp has since gained a momentum of its own over the years. The list of participants this year revealed a blend of first time attendees as well as regulars drawn to the camp every year. While participants like Sujatha Mohan, a busy dance teacher at Chennai, and Sai Santosh, an up-and-coming dancer, waxed eloquent over the access to the scholars and experts the camp provided, other enthusiasts were there for the ‘break from the daily routine and a chance to soak in dance, music and more dance’. And of course, the sumptuous spread from early morning breakfasts to the dinners and “the kalyana saapaadu” as one dancer put it, organised by the Trust for all the participants, kept them energised through the day.

VEDAVALLI SPEAKS - The art of viruttam singing

Naadena vyajyate varnahpadam varnaat padaadvachah | Vachaso vyavahaaroyam tasmaan naadaatmakam jagat || says Sarangadeva in his Sangeeta Ratnakara. Syllables are derived from nada or sound, words from syllables, speech from words and from speech all activity in this world. Thus nada being the basis for everything else, we see that words are more appealing when recited or sung in a tune. In mythology, the Ramayana is known to have been sung by Lava and Kusa. Subsequently, the bhakti literature of the Alwar-s and Nayanmar-s was also mostly sung except for some parts composed only for recitation (iyarppa). The verses themselves mention that they were sung to tune – naa?um innisaiyaal Tamizh parappum Sambandhanukku ulagattavar mun talam inda tamiyane; and innisaiyaal paadi koduttaal narpaamaalai, and Kulasekharan innisaiyil mevi cholliya to name a few. Children’s rhymes when sung in a tune attract children better. We find that in the katha cults of Andhra and Maharashtra, apart from the songs sung in between for highlighting particular instances, many times the narration is itself recited in tune to make the story-telling more lively. Even the vegetable vendor’s cry follows a tune. The term ‘vrttam’ is a Sanskrit word that denotes ‘meter’, that is a particular rhythm to which a verse is set. In literature, metrics is a separate branch of knowledge. Metrics in Sanskrit literature deals with many vritta-s like Indravajra, Sardoolavikreeditam, Sragdhara, Arya, and Mandakranta, each of which has a separate form and identity of its own. These meters regulate the arrangement of syllables and words in poetry. Prose does not follow these and is not regulated by them. Tamil literature also deals elaborately with the metrics aspect. Here, the verses are broadly classified as ‘isaippa’ (those which are fit to be tuned and sung) and ‘iyarppa’ (those that cannot be set to tune). The Yappilakkanam says that ‘pa’ or verse consists of six parts called ezhuttu, asai, seer, talai, adi and todai, and is of four kinds – venpa, asiriyappa, kalippa and vanjippa. These four kinds of verses in turn have three branches each, namely turai, taazhisai and viruttam. Here we find the use of the term ‘viruttam’ denoting a particular type of meter alone. A vowel addition to the ‘vrttam’ of Sanskrit is also seen, making it viruttam.