CENTENARY FEATURE - The stage was his world by Vamanan

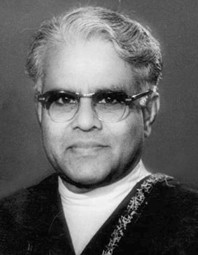

Exactly forty years ago, the noted stage actor T.K. Shanmugham made a spirited appeal for contributions to the celebration of the birth centenary of Pammal Sambanda Mudaliar, the amateur theatre personality who brought respectability to stage acting. It was in vain, and nothing worthwhile came out of Mudaliar’s hundred in 1973. Now it is the turn of Shanmugham himself to posthumously reach a century, but you can be sure his side is not going to win. Shanmugham was a nuts and bolts man who took his profession of acting and staging plays seriously. He would be a fish out of water in these times when the media can outdo him in theatrics.

Yes, he had a road and a drama hall named after him, and was conferred a ‘Padma Shri’ thanks to the efforts of his political mentor, M.P. Sivagnanam. But no ritual sleight of hand and mind can rest the spirit of a man who went on stage as a six-year-old and batted for half a century through thick and thin. He gave himself a breather only when his doctors asked him to give his heart a chance. Meanwhile, he came up with children’s theatre, which by the way introduced Kamal Hassan to stage-acting and the marvels of make-up, and also a half-biography up to 1948, based on a meticulously maintained diary.

Shanmugham’s demise in 1973 at 61 was premature, but he had packed a century’s events in half the time. Public memory seems to be poor when it comes to remembering Tamil Nadu’s greats of the past; our cultural icons are quickly consigned to the dungheap of history unless it is politically expedient to celebrate them.

SPECIAL FEATURE - Instinctive dancer, inspiring teacher by V. Ramnarayan

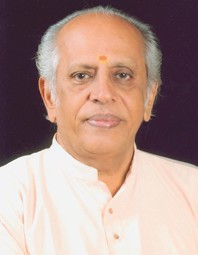

For those who started watching the Kalakshetra Ramayana series in the 1970s, Janardhanan and Venkatachalapathy as Rama and Lakshmana, Krishnaveni as Sita and Balagopal as Hanuman remain etched in their memories as inspiring examples of artistic excellence. The performances of these dancers were deeply touched by humility and devotion – to the art, their institution and their mentor. It seemed to the devout onlooker that he was in the presence not of performers but epic characters.

Closer inspection of course could have revealed that the actors were as human as anyone, but their self-forgetfulness on stage in the cause of their annual mission was undeniable. For those few hours and the days and weeks preceding them, all of them lived the characters they portrayed. In the years that Janardhanan played the prince of Ayodhya, he was Lord Rama to all, not a flesh-and-blood dancer-actor.

Janardhanan spent nearly half a century at Kalakshetra, as student, dancer, faculty member and finally principal of the Rukmini Devi College of Fine Arts at Kalakshetra. He retired as Professor Emeritus at the age of 62. In July this year, he was invited by his alma mater to help revive some of the dance-dramas choreographed by Rukmini Devi Arundale of which he was an integral part.

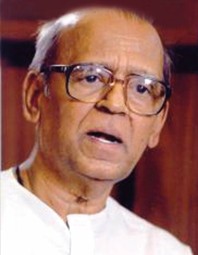

ESSAY - On art music by Dr. Ashok Da Ranade

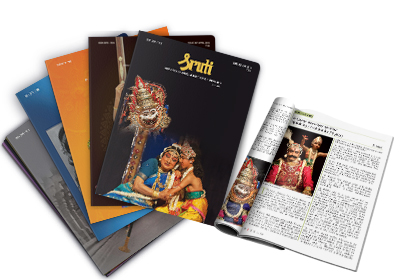

In its October 1991 issue, Sruti made a small but significant change bydropping the word “classical’ from its title. This change was prompted by a paper published by Dr. Ashok Ranade, who divided all music into five main categories, namely, primitive, folk, popular, art and devotional. The following are edited excerpts from an article (published in Sruti 104) based on a discussion with Dr. Ranade on the ‘Categories of Music’.

All music can be naturally organised into fundamental classes or categories. This leads to corresponding categories of kinds of experience of different musics. There can be no claims for universal validity for musical theories or judgements. In spite of inevitable and inbuilt overlaps, these categories do denote distinguishable and valuable experiential contents. Confusion of musical categories usually leads to wrong expectation, application of irrelevant criteria and inappropriate aesthetic judgement.

The fivefold classification of music

Primitive or tribal music

Folk music

Devotional music

Art (or Classical) music

Popular music

One must understand that these five categories need not exist in all societies concurrently and in equal proportions. In general, the more the number of existing musical categories, the more the degree of socio-cultural complexity in the society under consideration.

INTERVIEW - A cellist in Hindustani music by Saskia Rao-de Haas in conversation with Shrinkhla Sahai

Initially trained as a cellist in Western classical music, Saskia Rao-de Haas’s tryst with north Indian classical music took her to varied musical shores. While her virtuosity with the instrument developed under cello maestros Tibor de Machula and Ubaldo Arcari, her musical moorings expanded to new vistas under the mentorship of Hariprasad Chaurasia, Sumati Mutatkar, D.K. Datar, Deepak Chowdhury, Kaustav Roy and Shubhendra Rao.

In this conversation she reflects on her instrument, experiments, research and her journey towards a unique musical identity.

How did your musical journey start?

I was born in Holland and most people in my family are in music. My parents play the piano, my grandfather played the cello and my grandmother was a singer. When I was seven years old, I could choose my own instrument. I was deeply fond of the cello and I wanted to learn it.