A tall, distinguished man with a scholarly air walks into a sabha, to be immediately surrounded by eager young artists waiting to welcome him. We immediately notice his erect posture and elegant kurta as he smiles and greets the crowd around him. All his real life roles – of academician, dancer, musician, choreographer and teacher – are reflected in that one confident stride. Professor C.V. Chandrasekhar quietly slips into the hall where a young dancer is performing and takes his seat cringing at the fanfare his entrance has caused.

A Padma Bhushan awardee (2011), Professor Chandrasekhar retired from the M.S. University, Baroda, as Head of the Department of Performing Arts in 1992. Since then, several prestigious awards have followed – the Central Sangeet Natak Akademi award, Kalidas Samman, Nadabrahmam, and Sangeeta Kala Acharya, to name a few. Little did he know as a young M.Sc Botany student that he would one day be a beacon light in the Bharatanatyam world. Not only is Prof. Chandrasekhar one of the first few male Bharatanatyam dancers to dedicate their lives to art, but he has three talented women to share his artistic space – his wife and dance partner Jaya Chandrasekhar, and his daughters Chitra Chandrasekhar Dasarathy and Manjari Rajendra Kumar, who are established performers known for their creative and intelligent approach to the art form. If you happen to walk into his home in Chennai you cannot miss the friendly discussions on art going on between the dancing couple and their daughters.

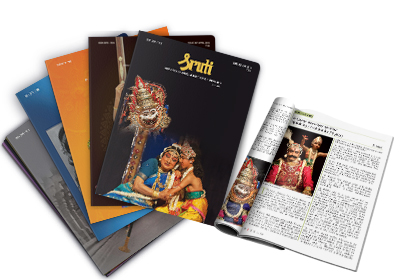

The Association of Bharatanatyam Artistes of India (ABHAI) confers the prestigious award of Natya Kalanidhi on Prof. Chandrasekhar on 20 October in Chennai. Sruti published an extensive interview of CVC Sir (as he is known in dance circles) in November 1989 (Sruti 62). Today we speak to this legend and ask him to share his thoughts on the artistic path he has taken and the changes and trends in the field of Bharatanatyam over the last few decades as he sees them. After all, not many can claim to have been part of the dynamic changes that Bharatanatyam has seen since the 1940s and to have performed the same repertoire of items at their arangetram and fifty years later.

As a boy of ten at Kalakshetra did you dream that you would one day receive the Padma Bhushan award?

(Laughs) Not at all. Actually I am not the first such awardee in the family. My father received the government-instituted Rao Sahib award in the 1940s – probably equivalent to today’s Padma Shri. As he was deeply interested in music, I was exposed more to music than dance from a young age. In fact, my sister recently ferreted out an old notebook which had a small song I wrote when I was young. I had written the lyrics, set the tune, and even had my mudra Chandrasekhar penned in it!

I began my formal training in dance at Kalakshetra in 1946, but I remember dancing to a sringara padam Velavare unnai tedi at a small function when I was seven years old. Some years later, MS Amma’s daughter Radha taught me a small dance item at home. So the seeds of artistic leanings were planted early in my life.

How did Bharatanatyam enter your life?

I was sent to Kalakshetra to study and learn music. When I was ten years old, Athai (Rukmini Devi) wanted me to train in Bharatanatyam as well. May be she heard reports of me constantly peeping into dance classes! I learnt the first tattadavu from Karaikal Saradambal who was then teaching in Kalakshetra. After that, Chinna Sarada (Sarada Hoffman) and Peria Sarada taught me for many years. I will never forget their meticulous training.

Any memories of your arangetram?

The event is vivid in my memory. Athai had set the date for it in 1950. Before that, I had taken part in dance-dramas – my first role was that of a kattiakaran in Kutrala Kuravanji. Can you believe, the total cost of the arangetram was only Rs. 520? The biggest expense was on the sari I wore, which cost 112 rupees! I still have the bills of expenditure. I had nattuvangam, vocal, mridangam and mukhaveena for accompaniment. In those days we did not use the flute and violin for solo performances. There was no compulsion to perform an arangetram. It was Athai’s decision and we merely went along.

Is there constant pressure today on Bharatanatyam artists to perform ‘something new’ – thematic performances and new choreography. It seems to be different in Carnatic music.

Well, the music scene is also changing slowly. Musicians are presenting thematic concerts. The ragam-tanampallavi is slowly becoming rare but I do agree by and large that music rasikas look forward to a traditional concert as compared to Bharatanatyam. There are many reasons. Firstly, among the overwhelming number of arangetrams these days, not all are up to standard. People’s exposure to Bharatanatyam is largely confined to these mediocre performances. Too much of anything can be tiring. Secondly, the audience base for music seems to be more learned than that for dance. Music is more accessible to people from a young age, and you do not have to attend a performance to cultivate taste. If your family is interested in music, your taste for it begins to develop at home – by listening to the radio and audio recordings. For dance, however, unless you make an effort to watch performances, the exposure is almost nil. The language of abhinaya requires some understanding and concentration on the part of the audience. All these factors have forced organisers to woo audiences by re-packaging the traditional format.

Is this a welcome trend?

It is important to reach out and create a new audience but it is just as important to preserve the quality of a margam. A thematic production or a dance-drama gives more opportunities for group work and to continue our tradition of story telling. However, the margam is designed to preserve the intrinsic qualities of our art form and bring out the nuances of the Bharatanatyam technique. Many dancers feel that margam is easy to perform and that not much thought needs to go into it. I strongly disagree. We cannot be careless when performing the traditional repertoire because it carries the essence of the art form. I too have choreographed many group productions – mainly during my teaching stint at Baroda University – but I enjoy the traditional items and have continued to perform them throughout my career. I think it is the responsibility of every serious dancer to ensure that the margam does not become obsolete. It is a continuous effort.

Does the higher level of improvisation in a music performance attract more people?

Each art form has its own limitations and strengths. There is less nritta improvisation on the Bharatanatyam stage because there is a whole team of artists involved. All of us do not have the luxury of working with the same nattuvunar or mridangist; some things have to be set to ensure synchronisation – this has its own thrill for the audience. Of course in abhinaya, we have the freedom to improvise and that should be encouraged in every dancer. In the beginning, there is more ‘chittai’ in the teaching because a young student has to understand how the body moves in a stylised way. Only after understanding this can improvisation occur. In some styles like Odissi, the movements are completely planned and set and the execution demands complete stylisation and control. Each art form has a different focus.

In music not everything is improvised as people believe. I know many musicians who memorise kalpana swarams and raga alapana that they present! The use of complicated calculations in kalpana swaram in kutcheris today means that more pre-planned patterns are used. Sometimes this takes away from the simplicity of spontaneous presentation and affects the raga bhava.

Everyone speaks of your anga suddham and nritta, but your abhinaya too has a special stamp. Can you tell us how you developed your own style over the years?

It has been a long journey. In the early days I used a lot of hastas in my abhinaya pieces. After some years, I felt that the mudras were only aids, that satvika bhava was what made abhinaya special. I found that a mere look could convey more than crowded gestures.

Recently, I was asked to perform a whole evening of abhinaya in Mumbai. It made me so happy that people finally saw more than ‘Araimandi Chandrasekhar’ (laughs). I enjoy abhinaya as much as I enjoy nritta. Today, dancers confuse abhinaya with mere storytelling, and sancharis have become synonymous with narrative episodes. An endless number of stories are woven into each line of the pada varnam. To explore the emotion and poetry of the lines is more important. The crux of Bharatanatyam lies in the sensitive portrayal of emotions. It is not necessary to have a dramatic story in every sanchari.

What is your advice to dancers who are frustrated because of lack of performance opportunities and recognition?

It took me decades of hard work to achieve what I am in this field, and that is why I tell dancers not to be in a hurry or get frustrated if they do not gain recognition immediately. I am glad that I continued to practise and dance even when I was not performing regularly. Even today I do so when there is no performance around the corner. The other day, two ladies came and watched me practice at home. I was playing the music and at one point stopped to rewind and redo a jati which was not correct. One of them remarked in amazement: “Sir, you are like a student stopping to correct yourself and repeating it till it is right!” I said, “Well, that is why we call it practice.”

You have to learn to love the art form and demand perfection from yourself. Once you gain recognition, you have a greater responsibility to maintain standards.

Dancers today are dabbling in many areas – performance, research, choreography.

It is important for dancers to be well read and informed. In today’s world, it is also important to work in many areas in dance. However, we must remember that not everyone has the inclination to be a researcher or a performer. It also takes a different kind of skill set to be a teacher.

It is important at one point in your career to decide which area you want to master. That does not mean a performer should not study or vice versa but she has to recognize her limitations. For example, I was a qualified professor at Baroda University and technically could guide anyone doing a Ph.D. However, when students or researchers approach me I tell them that while I can help them in certain areas, I may not be the right person to guide them the way a scholar can.

We have to self-assess our abilities at every stage. This will help us understand that our learning does not make us masters in the field. Some of the learning and experimenting we do on the way simply add depth to our own understanding. Scholarship has influenced me greatly.

As a person who has seen dance evolve over many decades, please share your thoughts on the current trends in Bharatanatyam.

There are many good changes in the field. The students are bright, inquisitive and probably smarter than our generation. My one plea to all dancers is to hold on to the basic grammar of Bharatanatyam. By this, I do not mean bani or style. A bani is only an accepted way of movement which has over the years been followed by groups of people. Sometimes, however, in the name of bani even bad technique receives authentication. I have always been open to styles and do not believe that one is superior to the other. Each style has its own beauty and there is no need to be rigid about asserting one’s own bani as the ‘correct’ one. We confuse our students by setting pre-conceived ideas of beauty. Instead we should look at movement beyond the artificial borders we have created and see how we can preserve the beauty of the Bharatanatyam form. We must have an open mind and a less critical eye because there is something to learn from everyone.

Today we are exposed to so many dance forms and each artist thinks that the other form is more appealing! As a consequence, the movements of one style are freely incorporated into the other. If this trend continues, there will come a point when all classical forms will look the same. Odissi abhinaya is naturally stylised, Kathakali is dramatic, and Mohini Attam and Kathak have subtlety as their trademark. It is important that each style retains its stamp. The same goes for aharya. Conviction about your art form is important. We must not succumb to popular trends or play to the gallery all the time.

We must slow down in our work. It takes a lot of thought and creativity to do something new. How can you sustain and be creative if you are working on a new project every few months? Reworking an old item or a production is in itself a creative process. You will look at the same work you created a few years ago with very different eyes today. If we want to improve ourselves and add depth to our creative process, then this re-searching is important. I don’t see how the numbers make a difference. Just learn to love the art form you have chosen. That In itself can be more fulfilling than all the awards you will ever receive.

(Anjana Anand is a Bharatanatyam dancer and teacher)