Annapurna Devi

Some geniuses become legends in their lifetime even if they shun fame and choose to live in the shadows, away from the harsh glare of the arc lights and publicity. One such exemplary artist is Annapurna Devi, born Roshanara Khan, daughter of the founder of the Senia Maihar gharana, the famed Sarod maestro Ustad Allauddin Khan. At the time of her birth in April 1927, her father was the court musician in the royal court of Maihar, a small princely state in British India, now a part of the state of Madhya Pradesh in central India. Maharaj Brijnath Singh, Raja of Maihar, named the little girl Annapurna Devi, as she was born on the occasion of Chaithi Purnima. She came to be known by this moniker throughout her brief but scintillating career.

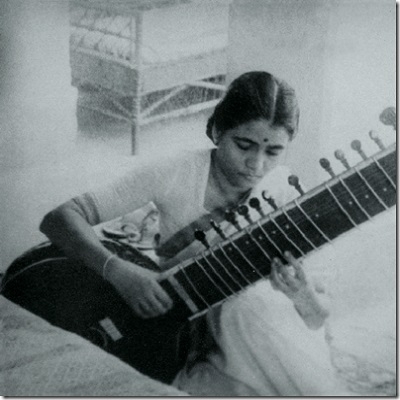

In the Indian classical music fraternity, the genius of Annapurna Devi has achieved the status of part mystery, part mythology. But her status as one of the greatest living exponents of the sitar and surbahar is unchallenged.

Music ran in her blood, being the daughter of an accomplished artiste and the niece of Fakir Aftabuddin Khan and Ayet Ali Khan, both established musicians in Shibpur, now in Bangladesh.

The story goes, so to say, that Ustad Allauddin Khan in line with the thinking of his orthodox faith, decided to train only the male progeny of the family in music. While her younger brother Ali Akbar Khan, an accomplished sarod maestro in his lifetime, was receiving lessons from their father, young Annapurna watched from behind closed doors and imbibed the lessons in her heart. One day, Ali Akbar Khan floundered on a particular note and young Annapurna not only corrected him but effortlessly sang a flawless rendition. The amazed father, who noticed this, handed her a tanpura and asked her to sing. The young girl’s soulful voice melted the genius; with tears streaming down he began to teach his talented and versatile daughter the intricacies of classical music. Thus began her taalim, with rigorous dhrupad training.

While understanding the shy nature of his daughter, Allauddin Khan also recognized the inherent talent in her. He also gauged the depth of intensity of her music and took it upon himself to teach her the surbahar, a larger and more difficult to play cousin of the sitar. The strains of the surbahar were dying out and Allauddin Khan knew in his heart that he wanted for his ‘guru’s vidya’ to have continuity and felt no one better than Annapurna could do that. He knew she would take it to the world one day. He was a hard and impatient taskmaster and his raging tempers were well documented but the soft and gentle nature of Annapurna always won him over and she was often the connecting link between him and his other disciples. One of them was Ravi Shankar, a young man keen to learn the sitar and make his mark on Hindustani classical music. Annapurna, Ali Akhar Khan and Ravi Shankar made the special trio that Allauddin Khan believed would carry his legacy forward.

Annapurna’s genius soon made her an accomplished surbahar player and she outclassed most of her male counterparts with her superlative performances. She even began teaching some of her father’s disciples guiding them in the intricacies and techniques of instrumental performances.

A marriage ensued between Annapurna and Ravi Shankar; not many facts are known about this except that the marriage lasted around two decades and the couple had a son Shubhendra Shankar, who was also trained in the sitar by Annapurna. Annapurna accompanied her husband on stage performances receiving applause and appreciation for her scintillating performances. Those who heard her perform Raga Kaushiki spoke of the legend of the only surbahar player in the world at baithaks and mehfils and came in large droves to hear, to never forget and to leave in awe. Her fame and popularity put the marriage through rough patches and the final breakup came in 1962. Many events after the break-up and the death of her son took a heavy toll on Annapurna’s gentle nature.

Her withdrawal from the world of classical music was as unceremonious as her entry. Taking a vow to never perform in public again and shrouding her music in silence forever, she shut herself away from public scrutiny into her own private world which only a privileged few had access to. However, anyone who came to her with the sincere desire of learning music found in her a willing teacher.

Maestros of the calibre of Aashish Khan Debsharma, Biren Banerjee, Hariprasad Chaurasia, Nikhil Banjerjee, Pradeep Barot, Amit Bhattacharya, Basant Kabra and Nityanand Haldipur, owed a great deal to her inspiring and unsurpassed knowledge of musical notes be it the sitar, surbahar, sarod or the flute.

Nothing has been able to draw her out from this shuttered world; not the Padma Bhushan in 1977 nor the Sangeet Natak Akademi award in 1991.

Her only touch with the outside world is her close association with the Acharya Allauddin Music Circle, set up in memory of her late father to promote Indian classical music.