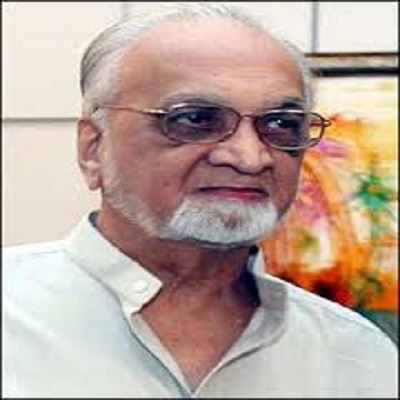

Vijay Tendulkar: unflinching gaze

Vijay Tendulkar who passed away in Pune on 19th May 2008, delivered the keynote address for the biannual all-America convention of Marathi speakers five years ago. He spoke not about literature, drama or cinema but about the virtues of charity, generosity and kindness. He argued that more often than not, charity was motivated by self-interest. When the giver gave his name to his gift, he was telling the world, look how charitable I am. The same was true of those who did favours to others expecting them to be obliged forever. Such charity and such favours were better not done. It was a profoundly purist viewpoint which did not go down too well with many of his listeners. Some people suggested snidely that the speaker was likely not to be a practitioner of what he preached.

The fact is that Tendulkar was not preaching. He was merely stating facts as he saw them. He was not preaching because it was not his practice to preach. A preacher, by the very act of preaching, puts himself above those to whom he is preaching. Tendulkar never did that. He always counted himself as one amongst many. He observed himself as he observed others. His autobiographical writings are evidence of his total honesty and candour in speaking about himself.

Tendulkar was a quiet man. He did not believe in a public display of emotions. One of the most poignant sights I recall was after his daughter Priya’s untimely death. During a condolence meeting organised by her friends and admirers, he sat quietly, stoically beside her framed photograph while people paid their respects to her, shook his hand and went away. His own funeral was marked by the same quietness. In keeping with his wishes, the media had been requested not to photograph him or the funeral. Even the State’s wish to give him a funeral that befitted his status as Maharashtra’s leading, often controversial litterateur, one whose work had put India on the world map, was turned down. There were no rituals, no weeping, no speeches. Just a solemn and dignified farewell.

I mention all this because, to be a great playwright is one thing; but to be a man who lives by his principles till his last breath in our corrupt times is quite another. There was no disparity between what he believed and what he practised. The seamlessness of belief and practice extended to his work. Not in 50 years of writing did he write a single word that did not represent his honest beliefs, his impartial observations, his understanding of and compassion for all human beings, including criminals and other wrong-doers.

If one is to answer the question, what did Tendulkar give to the world of Indian theatre, the answer would be, plays that looked at life straight in the face without flinching. If one is to answer the question what did he give Marathi theatre, it would occupy volumes. But putting it in a nutshell, I would say, he gave Marathi audiences their first experience of realism. He created men and women of flesh and blood. He gave them a language that belonged uniquely to them. He gave actors the chance to enrich their idiom. Actors who were trained to project their voices, assume dramatic postures and declaim were totally lost when speaking his lines. There was no drama there, no flamboyant flourishes, no heightened emotions or hyperbole. His dialogue was understated. But the spaces that he created between words and lines carried more dramatic tension than the words themselves.

A pause in drama is as pregnant as a held note in music. Just as a held note gradually releases a multitude of sruti-s, a pause in a play releases unexpected shades of meaning. It also contributes to the rhythm of the whole. Unless actors catch this rhythm, Tendulkar’s lines are likely to sound quite banal. Satish Alekar, whose plays Mahanirvan and Begum Barve are modern classics in the same bracket as Tendulkar’s Shantata Court Chalu Ahe (Silence! The court is in session), Sakharam Binder and Ghashiram Kotwal, was selected to play the male lead in Tendulkar’s one act play Olakh (Getting acquainted) when he was at college. Alekar says, “I found it very difficult to enter the character of the man I was playing. I found the dialogue very boring. I did not find anything dramatic in the play. There were pauses all over the place. The director would tell me, ‘If you enter deeply into the character you will find that the pauses get automatically filled with your expressions and body

language at the time’. But what I actually did was to fill the pauses by counting numbers in my mind.”

Gradually over time, actors learned how to make Tendulkar’s silences speak.

Music is expected to elevate the listener. Realistic drama should bring the audience down to earth. The kind of mainstream drama that Tendulkar and his colleagues opposed at the beginning of their careers, was full of conventional notions and sentimental cliches of middle-class thinking. It flattered the middle-class by covering up its hypocrisies and endorsing all its values. Tendulkar did the opposite. He posed questions. Do you think we are peace-loving, civilised and non-violent, he asked? Then there is Shantata Court Chalu Ahe. Here is a woman who has been made pregnant by a colleague and abandoned. So what do we, her other colleagues do?We put her in the dock and peck at her viciously till she collapses from the sheer fatigue of defending herself. That is how we can be.

Do you think families are noble units of society? Then here is Gidhade (Vultures) in which a family of brothers, sister and father are ready to kill each other for the sake of property. Do you think marriage is sacrosanct? Then here is Sakharam Binder who offers shelter in exchange for wifely duties to women who have been thrown out of their homes by husbands who clearly do not think marriage is sacrosanct. Do we Marathis consider Peshwa rule our golden age? Then here is a little story about how our icon of statesmanship, Nana Phadanvis served his own ends by creating a monster called Ghashiram Kotwal who ran rampant over Pune city while his power lasted.

If these plays had been fantasies, the middle-class audiences would have remained unperturbed. But they protested violently because Tendulkar had got under their skins with his unnerving questions and had forced them to look at a less than flattering reflection of themselves.

Ashis Nandy puts succinctly what Tendulkar did to his audiences. Towards the end of his preface to Tendulkar’s film script The Last Days of Sardar Patel, he says, “Tendulkar… never fails to make you feel that you have entered a dentist’s chamber with an undiagnosed abscess in the molars.” People are afraid of dentists. Many were afraid of Tendulkar.

The author is a well known theatre critic, writer, translator, playwright and columnist.